Living Legacies: Do Dead Cancer Cells Fuel Metastasis?

UAB Medicine Magazine, Summer 2011

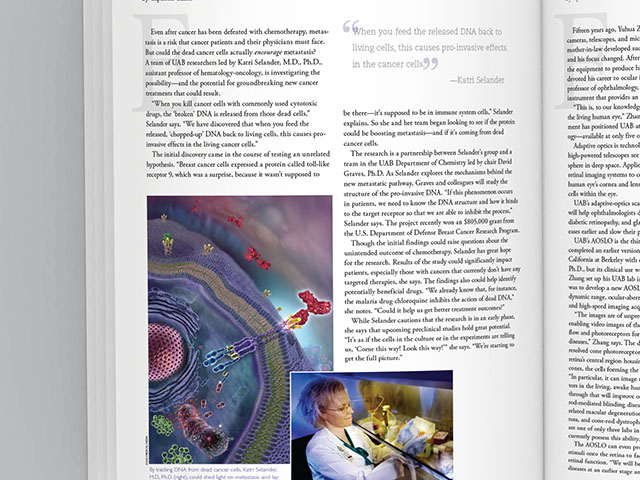

Even after cancer has been defeated with chemotherapy, metastasis is a risk that cancer patients and their physicians must face. But could the dead cancer cells actually encourage metastasis? A team of UAB researchers led by Katri Selander, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of hematology-oncology, is investigating the possibility—and the potential for groundbreaking new cancer treatments that could result.

Even after cancer has been defeated with chemotherapy, metastasis is a risk that cancer patients and their physicians must face. But could the dead cancer cells actually encourage metastasis? A team of UAB researchers led by Katri Selander, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of hematology-oncology, is investigating the possibility—and the potential for groundbreaking new cancer treatments that could result.

“When you kill cancer cells with commonly used cytotoxic drugs, the ‘broken’ DNA is released from those dead cells,” Selander says. “We have discovered that when you feed the released, ‘chopped-up’ DNA back to living cells, this causes proinvasive effects in the living cancer cells.”

The initial discovery came in the course of testing an unrelated hypothesis. “Breast cancer cells expressed a protein called toll-like receptor 9, which was a surprise, because it wasn’t supposed to be there—it’s supposed to be in immune system cells,” Selander explains. So she and her team began looking to see if the protein could be boosting metastasis—and if it’s coming from dead cancer cells.

“When you feed the released DNA back to living cells, this causes pro-invasive effects in the cancer cells. —Katri Selander”

The research is a partnership between Selander’s group and a team in the UAB Department of Chemistry led by chair David Graves, Ph.D. As Selander explores the mechanisms behind the new metastatic pathway, Graves and colleagues will study the structure of the pro-invasive DNA. “If this phenomenon occurs in patients, we need to know the DNA structure and how it binds to the target receptor so that we are able to inhibit the process,” Selander says. The project recently won an $805,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program.

Though the initial findings could raise questions about the unintended outcome of chemotherapy, Selander has great hope for the research. Results of the study could significantly impact patients, especially those with cancers that currently don’t have any targeted therapies, she says. The findings also could help identify potentially beneficial drugs. “We already know that, for instance, the malaria drug chloroquine inhibits the action of dead DNA,” she notes. “Could it help us get better treatment outcomes?”

While Selander cautions that the research is in an early phase, she says that upcoming preclinical studies hold great potential. “It’s as if the cells in the culture or in the experiments are telling us, ‘Come this way! Look this way!’” she says. “We’re starting to get the full picture.”