Artificial intelligence is a handy tool. It’s also somewhat misleadingly named tool — as much emphasis as we tend to put on the “intelligence” part of it, it’s the “artificial” part that could benefit from more emphasis. So I’m going to talk about AI, and as befits such a thoroughly modern and high-tech subject, I’m going to start by talking about this chick named Shirley circa 1950.

Shirley you jest

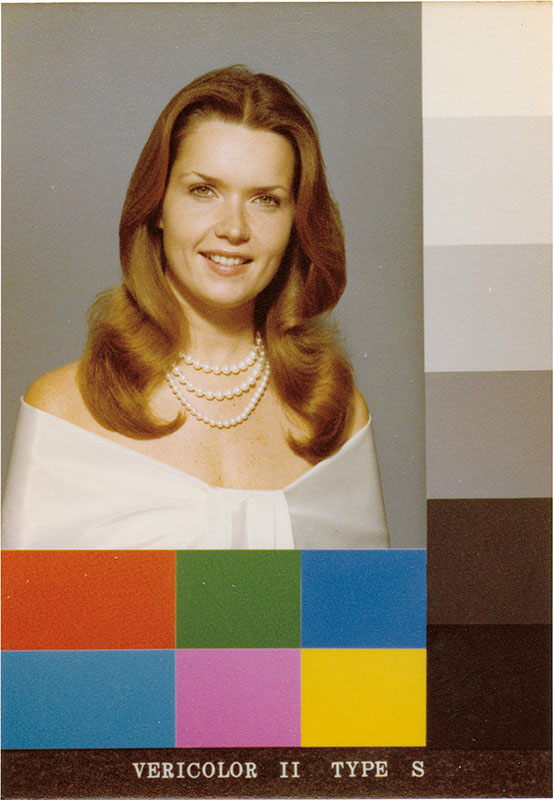

Back in the mid-1950s, when commercial photo processing was just becoming a thing and Kodak was sending its first color photo printers out into the world to independent photo labs, the company came up with a clever calibration kit. It sent out color prints and unexposed negatives, and when you processed the negatives such that they matched the prints, congratulations! Your printer was calibrated properly.

Originally, all the prints were photos of Kodak model Shirley Page, who would have to sit for literally hundreds and hundreds of photos. Over time, of course, other models were used as well, all of them smiling, bright-eyed, brunette, white, and named Shirley. (Okay, not that last one. But the prints were still called “Shirley cards.”) The result? Decades and decades of perfectly-exposed white people and Black people who looked like they were photographed by Annie Leibovitz (YEAH, I SAID IT). Kodak didn’t release its first non-white Shirley card until the 1970s (and even then, it was the complaints of furniture companies and chocolate makers, not BIPOC camera owners, that led to improvements in products and processing that resulted in film that worked for darker skin tones).

There’s no such thing as a racist photo printer. It’s a machine. They have no motivation. (A photographer who never bothered to learn how to light dark skin? That’s another story.) But a printer calibrated based on a flattering photo of a white model, shot by a white photographer, for use with a product that was, at the time, owned mostly by white people, was inevitably going to produce poor results for anyone who didn’t look like Shirley.

Which brings us, naturally, to Google Cloud Vision seeing bearded women in 2020.

Bearded ladies

This week, marketing agency Wunderman Thompson’s data group released a study looking into how different visual AI systems handle images of men and women wearing PPE. They took 265 images each of men and women with an assortment of settings, mask types, and photo quality levels and ran them against Google Cloud Vision, IBM’s Watson, and Microsoft Azure’s Computer Vision to see what the systems thought they were seeing.

All of the systems struggled to spot masks on the faces of men or women, although they were twice as good at identifying male mask-wearers than female. The AIs had some interesting thoughts about what they were seeing.

- Microsoft was more likely to ID the mask a fashion accessory on a woman (40%) than on a man (13%).

- It was about as likely to identify it as an outrageous amount of lipstick on a woman (14%) as it was a beard on a man (12%).

- Watson tagged the mask as “restraint/chains” and “gag” on 23% of women’s photos and just 10% of men’s.

- Google identified PPE on 36% of men and just 19% of women.

- On 15% of men’s photos and 19% of women’s, it mistook the PPE for duct tape.

An AI is only as good as the human being programming it and the data set it’s being trained with. What does it say about both that Watson looks at a woman in PPE and sees her in restraints nearly a quarter of the time, or that Google Cloud Vision is more likely to think a woman has duct tape over her mouth than a surgical mask?

Not what you think

What it doesn’t mean is that some dickhole at Google was drunk at the office one night top-loading Cloud Vision’s training set with women gagged with duct tape. It does mean that an AI is only as good as the data set available to it, and those data sets exist in a biased world. In their report, WT contrasts Google Image search results for “duct tape man” and “duct tape woman.” If “duct tape man” is more likely to turn up a photo of a man in an ill-advised Tin Man costume and “duct tape woman” is more likely to have tape over her mouth and mascara running down her cheeks, then yes, an AI that feeds on those same images will get some ideas about what a woman with half her face covered might be up to.

WT also mentions Tay, Microsoft’s AI chatbot that went from “hello world” to “9/11 was an inside job and feminists should die” in just 16 hours because of the trolls it was interacting with and the data it was scraping. I’m confident that Tay’s engineering team didn’t, collectively, believe those things. But I’ll bet it didn’t have a lot of women on it, ‘cause they would have warned Tay about the “feminists should burn in hell” crowd before she went live.

When visual AIs are given training sets that are mostly white men, they’ll provide more accurate results for white men than for people who aren’t one or both of those things. When a neural network is trained from a dataset full of racial slurs and crude anatomical language, it’ll be more likely to decide that a woman holding a baby is a… never mind. When a black teenager is murdered, and the news posts the most aggressive-looking photo it can find on Facebook, and a white college student is convicted of sexual assault, and the news posts a smiling photo from fraternity picture day, human beings aren’t the only ones who get a messed-up idea of what criminals and victims look like.

That doesn’t mean AI is inherently evil. It just means it isn’t any less flawed than the rest of us. AI isn’t smarter than we are — just faster. And so we shouldn’t depend on AI to do anything better than we do — just faster.

Faster, Pussycat

As pointed out by TheNextWeb, algorithms are better at telling you the past than the future. Predictive policing systems tell you where arrests have been made, not where crime is likely to happen. Sentencing algorithms tell you how sentences have been handed down, not what sentences are warranted. Hiring algorithms tell you which candidates have always been hired for a position, not which ones will do the job best. So if you want to get what you’ve been getting, but faster and with less effort, an AI trained on historical data is a great way to do that.

Just two months ago, IBM announced that it’s getting out of the facial-recognition game, because of the potential for bias and, thus, for their technology to be used in ways that violate people’s privacy and human rights. (I mean, if it can only tell a woman’s wearing a mask five percent of the time, maybe visual AI isn’t its strength anyway, but that’s neither here nor there.) But that’s an important reminder: This is a highly subjective tool with a huge potential to tell you exactly whatever it is you want to hear.

Think of visual AI, and other kinds of AI, like a self-driving car: They’re fun, and they can be handy tools when you need to get somewhere and want to be able to answer email while your car does its own driving. But if it’s really, really important that you get to the hospital before your appendix ruptures, your best bet is to have an actual human behind the wheel. It’s better than arresting the wrong person because your facial recognition system thinks all Black people look alike.

Um, I mean, getting into an accident. It’s better than getting into an accident.