RBG has never been photographed in her “Rise and Grind” collar, but no one has proved to me she doesn’t have one. (Credit CNN Films/Kobal/Shutterstock)

This week, we lost a part of jurisprudential history, a defender of human rights, a trailblazer for women, and, more importantly, a strong and brilliant woman. Ruth Bader Ginsburg has died at age 87. I and most people I know kind of wished she would prove immortal, and it damn near looked like she might be, but you really can’t blame her for not being that, and the legacy of everything she’s given us will stand in her absence.

She fought through uninterrupted personal adversity all the way through law school, fighting through gender discrimination throughout her legal education — scolded for taking a man’s spot at Harvard law — and early career, standing against gender discrimination on behalf of women and men, arguing in front of the Supreme Court she’d ultimately serve on. That determination pervaded her life, even as she was undergoing chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer, or recovering from surgery for colon cancer, never missing a day of oral arguments. She was inspirational to women and set a standard that no human being should actually be expected to reach but is definitely something to reach for.

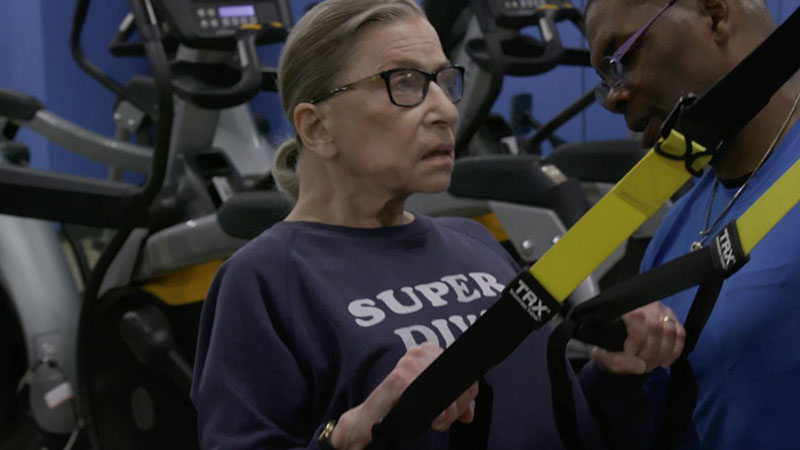

And she was a badass. Basically up until her death, she worked out with a personal trainer, lifting weights in sheer defiance of physics. (Do you even lift, Breyer?) In 2018, we learned that RBG had a full wardrobe of jabots — that’s the official name for those fancy collars she wore over her robes — and not only that, each collar means something different. Among others, she has her white favorite collar, a yellow “majority opinion” collar, and, of course, her famous “dissent collar” (which, totally coincidentally, she also wore to sit on the bench the day after Trump was elected, even though they weren’t making any decisions that day). Maybe we all should wear items of clothing that warn the world if maybe it isn’t the day to off with us.

She was also, of course, a writer, and she’ll live on in the decisions she wrote that will be enshrined in law through her Supreme Court decisions.

Bring out the collars

Justice Ginsburg was the author of numerous decisions for historic cases, and she was also the author of many stunning dissents, some of which she read from the bench, like a boss, making sure her opinions about justice for the people became a part of history. She was known for writing colloquially, eschewing formal legal language to make her opinions more accessible and, in that way, more powerful. Here are just a few of her significant responses.

Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., Inc.

Final vote: 5-4 for the defendant

Her position: Dissenting

In 1996 (with the final decision to be made in 1997), the court saw the case of Lily Ledbetter, who’d discovered that her paycheck at the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. was significantly less than the paychecks of her comparable male counterparts. And as her coworkers were receiving raises and promotions, she was being left behind. But she discovered this in 1998, as she neared retirement, nearly 20 years after her hiring in 1979. She argued that discrimination was discrimination and the company was behind in nearly two decades of payments. The state argued that it was more than 180 days since Goodyear had decided to thusly discriminate against her, thus the basis of “no takebacksies.”

In writing the court’s decision, Justice Samuel Alito reported the determination that if Ledbetter had discovered, and filed suit over, the pay disparity within 180 of her hiring, she might have a case. But because she hadn’t, she didn’t. The fact that she was receiving paycheck after paycheck that discriminated between her coworkers’ pay and hers was, apparently, NBD. Justice Ginsburg disagreed, saying:

It is only when the disparity becomes apparent and sizable, e.g., through future raises calculated as a percentage of current salaries, that an employee in Ledbetter’s situation is likely to comprehend her plight and, therefore, to complain. Her initial readiness to give her employer the benefit of the doubt should not preclude her from later challenging the then current and continuing payment of a wage depressed on account of her sex.

On questions of time under Title VII, we have identified as the critical inquiries: “What constitutes an ‘unlawful employment practice’ and when has that practice ‘occurred’?” Id., at 110. Our precedent suggests, and lower courts have overwhelmingly held, that the unlawful practice is the current payment of salaries infected by genderbased (or race-based) discrimination—a practice that occurs whenever a paycheck delivers less to a woman than to a similarly situated man.

The Supreme Court might say Ledbetter wasn’t being discriminated against every single pay period for 19 years, but Ginsburg argued otherwise. You tell ‘em, Justice Ginsburg.

Olmstead v. L.C.

Final vote: 6-3 for the plaintiff

Her position: Affirming

“No, no, we’re good on this one.” (Credit Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

In 1999, the Atlanta Legal Aid Society went before the Supreme Court in defense of two women in Georgia who had been unjustly confined to a state-run institution. The women, who had developmental disabilities and mental illnesses, had been voluntarily committed to the psychiatric unit of the Georgia Regional Hospital. But even after treatment, and after mental health professionals determined that they were ready to move to a community-based program, the state confined them to that institution for years. Years.

By the time Olmstead made it to court, both women had been released to those programs like the doctors had said they should from the very beginning. But the state still had the power to re-institutionalize them at will at any time. They were out, but they weren’t safe. And while it had taken four years to get in front of the Supreme Court — the case had originally been filed in 1995 — the Supremes determined that the state didn’t have the right to keep the women confined simply because they had a disability. In her decision, Ginsburg wrote:

The identification of unjustified segregation as discrimination reflects two evident judgments: Institutional placement of persons who can handle and benefit from community settings perpetuates unwarranted assumptions that persons so isolated are incapable or unworthy of participating in community life, cf., e.g., Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737, 755; and institutional confinement severely diminishes individuals’ everyday life activities. Dissimilar treatment correspondingly exists in this key respect: In order to receive needed medical services, persons with mental disabilities must, because of those disabilities, relinquish participation in community life they could enjoy given reasonable accommodations, while persons without mental disabilities can receive the medical services they need without similar sacrifice.

The fact that a person has a disability doesn’t mean they lack the right to be treated as a human just like anyone else. Damn straight, Justice Ginsburg.

United States v. Virginia

Final vote: 7-1 for the plaintiff

Her position: Affirming

In 1996, the Supreme Court heard the case against the Virginia Military Academy’s policy to only admit men. The court agreed 7-1 that this policy was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, and Justice Ginsburg had the following to say about it:

Parties who seek to defend gender based government action must demonstrate an “exceedingly persuasive justification” for that action. E.g., Mississippi Univ. for Women v. Hogan, 458 U.S. 718, 724. Neither federal nor state government acts compatibly with equal protection when a law or official policy denies to women, simply because they are women, full citizenship stature — equal opportunity to aspire, achieve, participate in and contribute to society based on their individual talents and capacities.

The state can’t deny women the opportunity to achieve simply because they’re women. Bring it, Justice Ginsburg.

Gonzales v. Carhart

Final vote: 5-4 for the plaintiff

Her position: Dissenting

In 2003, President Bush (the W one) signed into law the deceptively named Partial-Birth Abortion Ban act. (Side note: “partial birth abortion” isn’t a thing.) The Act was deemed unconstitutional in three district courts on the basis that it didn’t give two shits — ahem, I mean it didn’t make any exceptions for the health of the mother, and that the government hadn’t provided any new evidence that would distinguish it from a previous Supreme Court ruling on the subject.

The court decision, as written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the Carhart side hadn’t provided any evidence that Congress didn’t get to ban the procedure, that a previous ruling had established that the state has an interest in “preserving fetal life,” and that banning this procedure that medical practitioners up to and including ACOG have deemed necessary for doing their job actually doesn’t constitute an undue burden on women’s autonomy over their own body or a risk to her health. Justice Ginsburg, naturally, disagreed, saying:

As Casey comprehended, at stake in cases challenging abortion restrictions is a woman’s “control over her [own] destiny.” 505 U. S., at 869 (plurality opinion). See also id., at 852 (majority opinion).2 “There was a time, not so long ago,” when women were “regarded as the center of home and family life, with attendant special responsibilities that precluded full and independent legal status under the Constitution.” Id., at 896–897 (quoting Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U. S. 57, 62 (1961) ). Those views, this Court made clear in Casey, “are no longer consistent with our understanding of the family, the individual, or the Constitution.” 505 U. S., at 897. Women, it is now acknowledged, have the talent, capacity, and right “to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation.” Id., at 856. Their ability to realize their full potential, the Court recognized, is intimately connected to “their ability to control their reproductive lives.” Ibid. Thus, legal challenges to undue restrictions on abortion procedures do not seek to vindicate some generalized notion of privacy; rather, they center on a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature.

A woman’s right to bodily autonomy is paramount, whether or not a court full of men think it is. Damn straight, Ruth. Speak the truth, Ruth.

Shelby County v. Holder

Final vote: 5-4 for the plaintiff

Her position: Dissenting

In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed to address racial discrimination in voting (which, at the time, apparently was considered “an insidious and pervasive evil which had been perpetuated in certain parts of our country through unremitting and ingenious defiance of the Constitution”). Various sections of the law banned practices that would abridge voting rights on the basis of race and that specific jurisdictions that maintained discriminatory practices and/or had low voter turnout needed extra supervision, and thus any changes to voting procedures would have to be “precleared” with authorities in Washington. You know, because if they make decisions on their own, they do racism.

In 2013, Shelby County, Alabama, argued that this was unfair because they were better now, for real. The Supreme Court’s ruling was that yeah, that’s bad, and Section 4 (the one that requires preclearance) was unconstitutional. The court’s decision, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, was that while back in ’66, “these these departures were justified by the ‘blight of racial discrimination in voting” that had “infected the electoral process in parts of our country for nearly a century,’” things are better now, because with the Act, “‘[v]oter turnout and registration rates” in covered jurisdictions “now approach parity. Blatantly discriminatory evasions of federal decrees are rare. And minority candidates hold office at unprecedented levels.’” So basically the “but we have a black president now!” argument established as legal precedence. Justice Ginsburg, you might be shocked to know, disagreed, saying,

Instead, the Court strikes §4(b)’s coverage provision because, in its view, the provision is not based on “current conditions.” Ante, at ___, 186 L. Ed. 2d, at 669. It discounts, however, that one such condition was the preclearance remedy in place in the covered jurisdictions, a remedy Congress designed both to catch discrimination before it causes harm, and to guard against return to old ways. 2006 Reauthorization §§2(b)(3), (9). Volumes of evidence supported Congress’ de-termination that the prospect of retrogression was real. Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.

Cool, yeah, racism is over, so we don’t have to protect BIPOC people from the very real discrimination and voter suppression that is still happening to this day. Except Ginsburg knew that, hey, maybe INSTITUTIONAL RACISM IS STILL A THING. FUCK ‘EM UP, RBG.

Her legacy

Justice Ginsburg’s passionate arguments also influenced cases for which she didn’t write the decision. In Safford United School District v. Redding, the court decided that the middle school was wrong to strip search a freaking 13-year-old girl on suspicion that she might be smuggling prescription-strength ibuprofen. And what’s almost as bad is that the male justices didn’t think it was a big deal. “How bad is this?” Justice Stephen Breyer said about a teenage girl being forced to strip down to her underwear because ibuprofen. Ginsburg, the only woman on the court, had to point out that the other justices “have never been a 13-year-old girl.” At least they finally came out on the side of the girl, even if it mystifyingly (read: not really mystifyingly) was the subject of debate.

If you happen to be a woman and/or BIPOC and/or LGBT and/or concerned about your reproductive freedom and/or personally invested in fair voting, you’ve lost a determined champion for your rights, and that is truly tragic. It puts a lot of pressure on us to fill the gap that she’s left, to the extent that we’re able, in whatever way we’re able. There never has been and never will be another Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and the 87 years we had with her are precious.

To the Honorable Ruth Bader Ginsburg, may your memory be a blessing. And to the Notorious RBG, mourn you ’til I join you.