Coronavirus panic serves no one — but you gotta admit, it’s pretty hard not to sometimes.

Within the week prior to this posting (March 2, 2020), the U.S. has experienced: the first community-spread cases of COVID-19 (the disease caused by the novel coronavirus) within the U.S., the first two COVID-19 deaths inside the U.S., and hard hits to all major stock indices amid global fear and uncertainty. It’s kind of terrifying, and it’s not likely to get any less so in the near future. Any words of comfort are welcome.

Well. Not any words.

Far be it from me to try to silence anyone who has something they feel they need to say in a time of concern and confusion. But a global-scale infectious disease outbreak isn’t like just any other opportunity to weigh in. When people are scared, they don’t think straight, they don’t always use common sense, and they don’t take time to fact-check, and — like the common cold in a patient with a compromised immune system — misinformation can go from dangerous to deadly.

(F’rinstance: Notice that I said “epidemic” up there and not “pandemic.” That’s because the World Health Organization has specifically chosen not to apply the term “pandemic” yet. (Yet.) The WHO carefully applies the p-word based on factors like geographical spread, disease severity, and societal impact, and while they’ve assessed the global risk level at “very high,” they’re not quite there yet. “Using the word pandemic now does not fit the facts,” says WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, “but it may certainly cause fear.”)

Healthcare workers are experiencing a shortage in protective face masks, in part because scared people are buying them out — even though the CDC doesn’t recommend face masks for anyone who isn’t sick or caring for someone who is sick. People of Asian descent are being abused and treated like disease vectors. Bad facts are dangerous. Irresponsible communication has consequences.

So if you want to comment on the ongoing coronavirus outbreak, I’m not saying don’t do it. I’m saying ask yourself these three questions first.

1. Do I have anything valuable to offer?

If the answer to this question is “yes,” then by all means, please offer it.

The unknown can be scary enough when there aren’t lives on the line, and accurate information can be very comforting. If you have experience, knowledge, or perspective that you find lacking in current discussions of the epidemic, please contribute. Make the world a better place by making it a slightly less bewildering one.

You don’t have to be an infectious disease specialist to have something worthwhile to say online (although if you are, I’d certainly push you to the front of the line). Maybe you’re just really good at understanding science and translating it for non-science audiences. Maybe you know things about international travel, or economics, or disaster preparedness, or mental health, or explaining complicated subjects to children, and can offer valuable insight in that area. Maybe you don’t have a lot of knowledge yourself, but you have a big platform and can use it to signal-boost people who do have a lot of knowledge and don’t have a big platform.

If none of that applies to you, though? If you don’t have anything to present that isn’t already out there, possibly in a better form than you’d be able to present it? Not presenting anything is a perfectly respectable — and responsible — option. There’s going to be a lot of information flying around over the coming weeks and months, and sorting through the noise to find the important stuff is going to be challenging. Weighing in just for the sake of weighing in makes it even harder to find that important stuff, and the chances of inaccurate or alarmist information getting out increases with every dubiously qualified contributor. There’s no shame in sitting this one out. Another opportunity will come around.

2. Do I have my facts straight?

Do you? Are you sure? Are you super super duper sure?

No, but really? Because in 2014, witting trolls and unwitting accomplices blamed foreign aid workers for the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, causing people to shy away from healthcare workers and allowing the disease to spread. In 2019, polio cases in Pakistan rose more than tenfold after a viral video spread the false claim that the polio vaccine was harmful. That misinformation was planted by people who knew better and disseminated by people who believed they were doing the right thing to help their neighbors in a time of crisis.

They weren’t, though.

This isn’t a “my guess is” or “I suspect that” kind of situation — it’s a kind of situation where wrong guesses are dangerous. Stick to what you know to be true, and be transparent about where your information is coming from. “They’re probably [X]?” Not so much. “When I worked for the state health department back in the ‘90s, we used to [X].” There you go. Go for clarity over cleverness, cite and link your sources, and date-stamp your data to make sure someone running across your post three weeks from now doesn’t mistake your stuff for something more up-to-date.

Also, be very, very, very careful about thirdhand information you share, even if it’s from someone you generally trust. Check any data against the CDC and the World Health Organization, and if it doesn’t square, don’t pass it along.

The more we see information floating around, the stronger our subconscious tendency to believe it’s legit — it’s called the illusory truth effect. Even after a falsehood has been debunked, we’re still more likely to remember seeing it before than we are to remember that it’s wrong. If there’s the slightest chance that what you’re about to put out into the world isn’t correct, just don’t do it.

3. Am I ready to keep engaging?

Unfortunately, this thing isn’t going to end any time soon, and once you make yourself a part of it, you’re a part of it. Once you make yourself a source of information, people are going to come to you for information. If you write a blog post tomorrow that is contradicted by new discoveries a month down the road, you need to be ready to post an update so your blog doesn’t suddenly become a source of misinformation. If someone in your comments section drops some inaccurate information, you need to be ready to set things straight. If someone in your comments section corrects your inaccurate information, you need to be ready to engage with them civilly and make any updates necessary.

Accuracy and timeliness in situations like this are far more crucial than they are for the average blog post. Your commentary on this subject is a commitment to not become another source of misinformation in a world full of it. If you’re not up for that responsibility — and that’s perfectly reasonable — it’s best to leave the commentary up to someone who is.

Go forth and comment. Or, y’know, not.

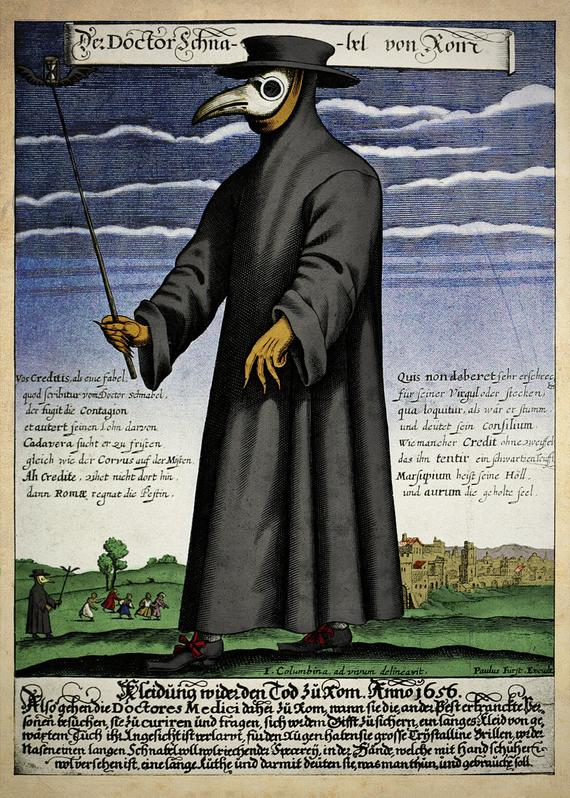

Still have a valuable contribution to make to the discussion of the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, and everything that goes along with them? Awesome. The world needs valuable contributions. Deciding you’re actually going to pass on this one? Also awesome. In choosing not to exacerbate the spread of panic and misinformation, you are, in your own way, doing a service to society. Not all heroes wear capes.

Either way, stay informed, follow the right sources, check your facts, and try to keep it together. And for the love of God, wash your hands. I mean, we know where they’ve been. That’s just gross.